Ray Hughes, who opened his first gallery in Brisbane, Australia in 1969 never brought an object into his home that lacked visual impact. His collecting habits were never on trend nor polite, but they were carried out with a passion and vigour that few collectors in Australia or further afield have matched. He was not encyclopaedic with his tastes but rather drew together strands of imagery from the hundreds of pieces of source material he accumulated on his travels abroad and in later years, largely immobile due to the diabetes which ultimately claimed him late 2017, courtesy of his voracious appetite for art periodicals and catalogues.

Ray’s first pieces were acquired in the late 1960s, tribal art from Oceania, Australian pop art by Peter Powditch and the works of his progressive stable of young painters in Queensland. The tribal interest would remain throughout the course of his life, fed both at the source in New Guinea or West Africa or in the Colonial context of galleries in Brussels, Paris ,London and indeed the salerooms of Sydney where he would often hunt.

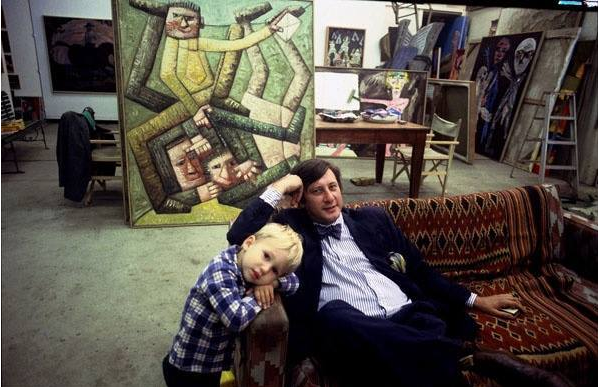

I often said of my father, who had no appetite for the trappings of wealth like wristwatches, jewellery, trophy paintings or fast cars, that if he could travel twice a year and spend every cent on lunch, German expressionist prints, African art, knickknacks, art books and if he was in an extravagant mood, business class air travel then he was happy. The joy of my teenage years was spent as my father’s enthusiastic travelling companion.

We once flew to Los Angeles where we researched contemporary African art at the Hammer Museum at UCLA, flew next to Chicago where be purchased a trunk load of Haitian voodoo banners, bought African Toys at Craft caravan in New York and via a week or so in Europe wound up in a Voodoo cult house on the banks of lake Lome in Togo haggling for their altar fetish figures after a ceremony of drumming, dancing, chicken decapitation and wonder.

A few years back as my father was becoming fairly frail I bullied the minders of a visiting Chris Dercon who was at that point the director of the Tate into visiting dad’s collection. The curatorial elites who so often turned their noses up at Ray’s brash dismissal of their minimal imagination were forced to endure a humiliating experience when Dercon publicly lectured a room at the Art Gallery of NSW that they should pay Ray’s ‘eye’ some attention. They never did, Dercon since lost his job, Ray died and most Biennales are still awful. Plus ca change?

My father’s eye was not particularly avant garde in a global sense, he just paid excellent attention, travelled, talked with smart people and listened. But it was often a good ten years ahead of Australia. In the case of his foray into Chinese contemporary art in the late 1990s he was indeed ahead of most dealers and collectors in the globe. On New Year’s Day, 2000 in a reception room at Uli Sigg’s schloss, when discussing a forthcoming trip to China, Ray found himself with the requisite coin in his slice of traditional seasonal cake for the legendary Swiss collector to turn to dad and very drily state: “But now you are the King, you must wear the crown”. Shortly after that trip he sold Kerr and Judith Neilson, founders of Sydney’s White Rabbit collection of contemporary Chinese Art their first piece from the Middle Kingdom.

Ray adored the interplay between his objects, from his Fred Williams gouaches playing off the line and composition across the room to his Joe Furlonger landscapes, his Han dynasty figures smiling at his beaming Luo Brothers cherubs, his Seydou Keita photographs alongside his carved objects; these would be softened by wild Asafo flags from Ghana or Anatolian rugs we collected one hilarious afternoon in Istanbul as I battled the onset of dysentery and he complained about not being able to find a bloody drink.

It has been tremendously emotional but also immensely fun to put together this collection for sale from dad’s estate. There are objects amongst the 550 or so works which I remember from the time of my early childhood, indeed some like the African car that I enjoyed playing with so much and which dad thought was the most extraordinary piece of surrealist sculpture one might ever own. Amongst these lots are some of the objects he adored most in the world. To give one an idea of what objects meant to the man, in his dying year, when it was clear that he was likely on the way out, we made a deal that I would take him out of his nursing home and buy him a big enough place that he could be surrounded by his pieces.

It was painful but beautiful to watch him go ultimately surrounded by the life of artworks that he made his own. The nature of this sale is to provide a complete encapsulation and record of a visionary collecting eye, as much for posterity as those who will purchase works from a unique collection.

For the record, he always resented my calling his collection of objects ‘knickknacks’. This is the boy who broke the Etruscan horse when playing cowboys back in 1988 and he never let me forget it.

EVAN HUGHES

April 2018