(Artsy Magazine)

When I was 17, I was finishing up my time at a boarding school for visual arts, and dreaming of spending my college years at an art school in New York. But in order to complete my portfolio for applications, I had to face one of my biggest artistic demons: drawing. So, I begrudgingly signed up for an introductory drawing class.

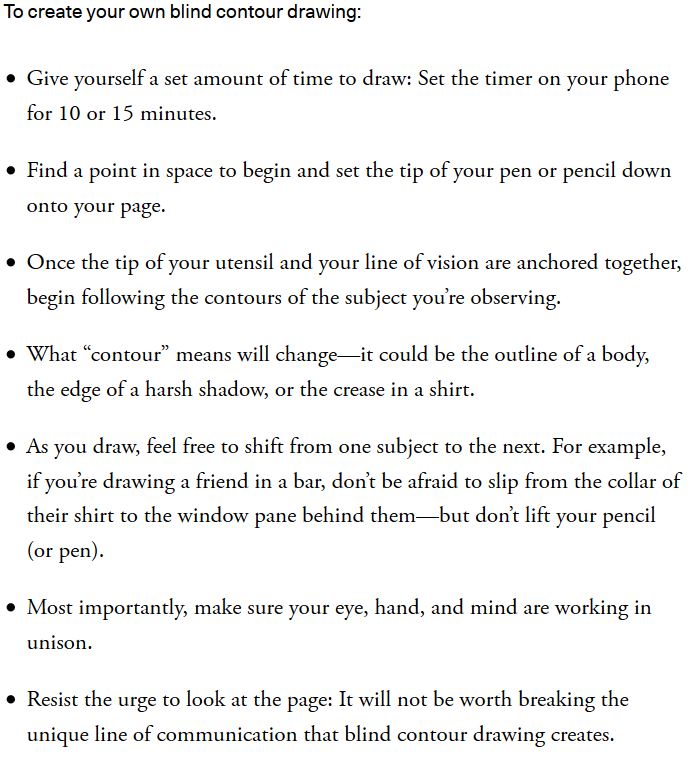

On the first day of the course, the instructor told us to get out a piece of paper and get ready to draw with a pencil. We were to raise our non-dominant hands up to our eyes, to inspect the wrinkles, curves, and shadows. As our eyes closely examined that hand, we were to use the other one to draw it, without ever looking down at the page or lifting the pencil.

The teacher set a timer for 10 minutes (which felt like an eternity), and when it rang, I looked down at my paper to find a frightening tangle of lines, which only vaguely resembled a hand. All I’d wanted was to make one solid drawing to prove myself capable of realistically portraying an object, but there I was, staring at my sweaty palm and making scribbles.

By the end of the semester, I’d made the mediocrestill-life drawing I was after, but this exercise—a staple of drawing classes, known as “blind contour drawing”—has continued to teach me lessons about drawing long after high school.

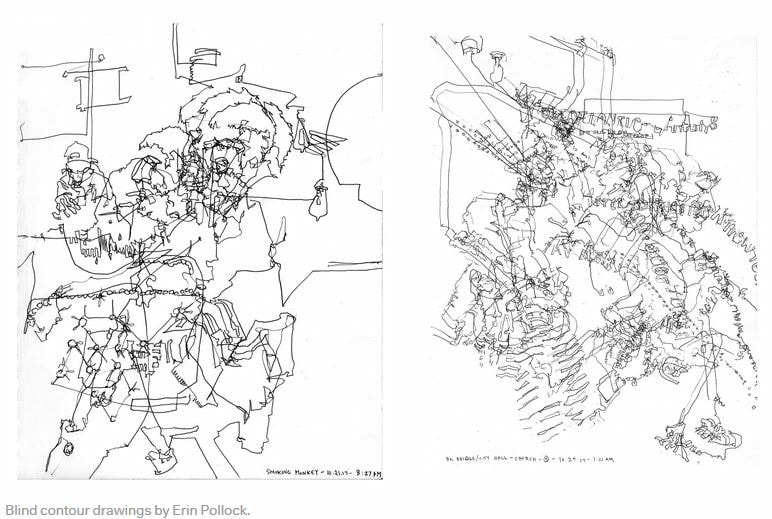

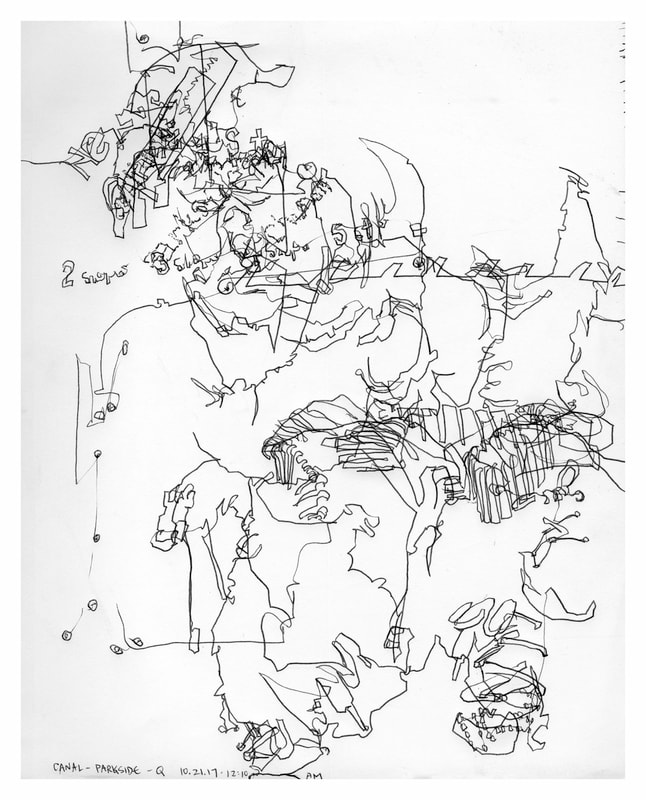

Instead of inciting anxiety, blind contour drawing is meant to help artists practice their observation skills, and for those who approach the technique with patience, it can even be a calming exercise. “It’s kind of like a meditation,” explained Erin Pollock, a fellow at the New York Academy of Art (NYAA). “The pen goes down on the page and your eye goes to a specific point in space and they move in sync.”

For Pollock, blind contour drawing is an opportunity to be more present, and slow down the process of looking. “I kind of think about [the tip of the pencil] like an ant, crawling around the contour of someone’s shoulder, then falling down to the table, and then up the side of salt shaker,” she said. “There’s just something about moving that slowly, and that focused, that makes you empty your brain of everything else.” The experience Pollock describes is shared by many artists––including the artist who popularized the exercise, Kimon Nicolaïdes.

In his 1941 book The Natural Way to Draw: A Working plan for Art Study, Nicolaïdes mapped out a variety of the exercises he used while teaching at the Art Students’ League in New York in the 1920s and ’30s. The first exercise he explained is what we now know as blind contour drawing (though he called it simply “contour drawing”).

“Focus your eye on some point––any point will do––along the contour of the model,” Nicolaïdes wrote. “Place the point of your pencil on the paper. Imagine that your pencil point is touching the model instead of the paper.” Once you’re convinced that the tip of the pencil is synonymous with the sight of the eye, Nicolaïdes told artists to begin to slowly follow the contour of the model across the surface of the page. “Be guided more by the sense of touch than by sight,” he instructed.

If you follow Nicolaïdes’s instructions, the chances of making a realistic drawing are slim. Instead, you’ll likely create a complicated mix of scribbles, lines, and suggested forms. “Everyone worries that [their drawing is] going to look silly or goofy or funny––but they will, and they’re hilarious,” said Sarah Sager, an alumnus of NYAA, who frequently practices blind contour drawing. In order to reap the maximum amount of benefits from the exercise, it’s best to remember that the technique is more about learning from the process than about producing a finished artwork. “As long as you’re really concerned about how beautiful it looks, or how correct it looks, you’re never going to make anything that has that ‘something’ about it,” Sager added.

In addition to setting unrealistic expectations, another mistake beginner artists make is taking their eyes off of their subject for long periods of time. For example, an artist drawing a still life of bananas might only glance up at the bananas for a mere second before returning their eyes to the page. This method of looking results in artists drawing from memory, rather than life.

But when done correctly––meaning, without peeking or removing the tip of the pen from the page––blind contour drawing gives artists an opportunity to portray exactly what they observe, instead of what they think their subject is supposed to look like. “A contour drawing is like climbing a mountain as contrasted with flying over it with an airplane,” Nicolaïdes wrote. “It is not a quick glance at the mountain from far away, but a slow, painstaking climb over it, step by step.”