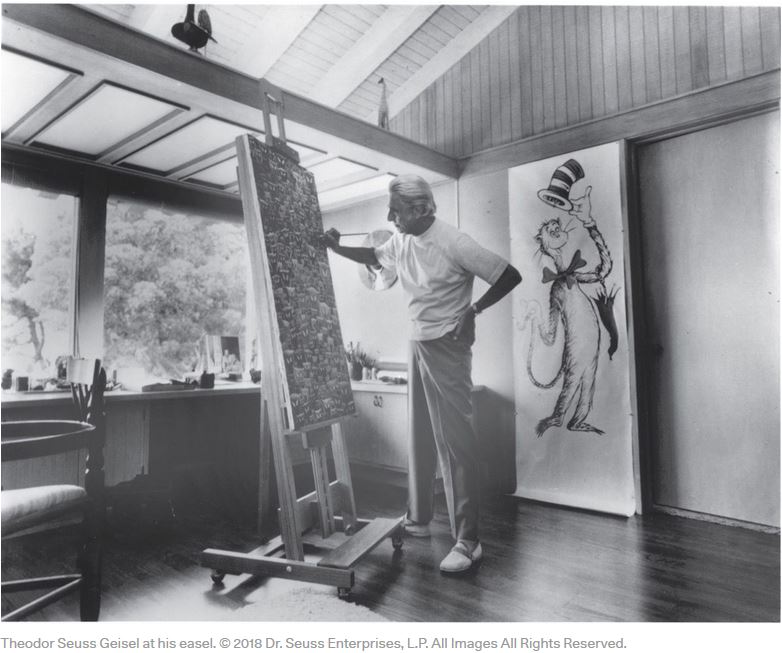

If you had stepped into the home ofTheodor Seuss Geisel just after his death in 1991, you would have found yourself at the entryway of the whimsical world of his pen name, Dr. Seuss. Inside the stucco exterior of his Spanish-style home in La Jolla, California, which he shared with his wife Audrey, Geisel had kept hundreds of drawings, paintings, and taxidermy-like sculptures of animals never classified by a taxonomist—at least not in this world.

Geisel—who once called adults “obsolete children”—had written and illustrated 44 children’s books under the moniker Dr. Seuss at the time of his passing, but he also spent his nights creating what he called his “midnight paintings,” a part of his practice he kept hidden from public view.

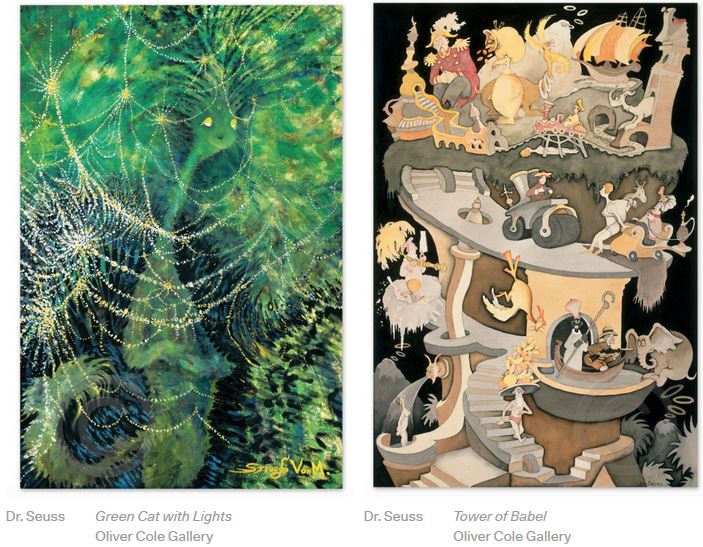

“It’s the type of art that he just loved to make by himself,” said Jeff Jaffe, owner and founder of Pop International Galleries, which is currently showing a collection of Geisel’s artwork in New York. “Some of it’s kind of racy, some of it’s politically naughty, some of it’s just fun.” One painting, Green Cat With Lights, is signed by a pseudonym, Stroogo Von M.; Geisel hung it in his home, pretending that he had discovered a new artist. According to Audrey, “On at least one occasion, a guest replied, ‘Oh yes, I’ve heard of Stroogo Von M.’”

Following Geisel’s death, Audrey donated many of his drawings to the University of California, San Diego. Then, in 1996, art dealer Robert Chase approached her with the idea to release limited edition reproductions of her late husband’s collection; he hoped to position Geisel as one of the great artists of the 20th century. “The Art of Dr. Seuss Collection” officially launched two years later, following a preview of the collection in 1997, with a small number of editions released annually for collectors. A retrospective of the collection has toured the country since 2004.

In her introduction to the collection, Audrey wrote: “I remember telling Ted that there would come a day when many of his paintings would be seen and he would thus share with his fans another facet of himself—his private self.” That facet of his work is just as otherworldly, with colorful, lyrical paintings featuring creatures who occupy the same Seussian universe, such as Every Girl Should Have a Unicorn (2001); illustrations that echo his time as an editorial cartoonist, like the tongue-in-cheek take on SoCal women, Martini Bird (2004); and more politically charged, darker compositions, such as Tower of Babel (2002).

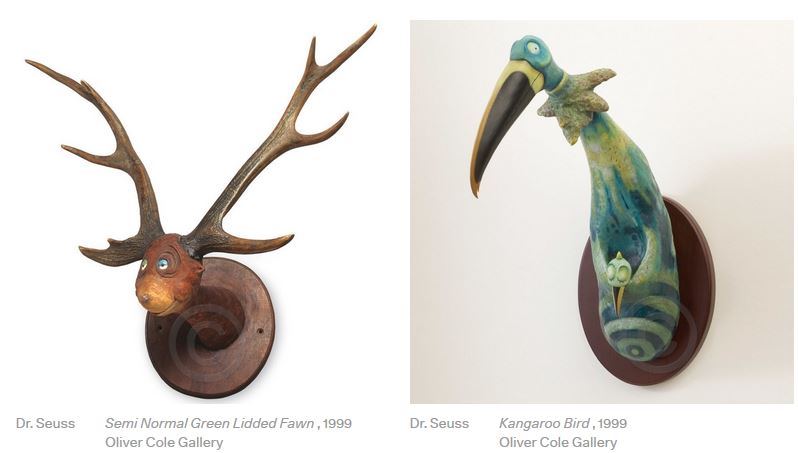

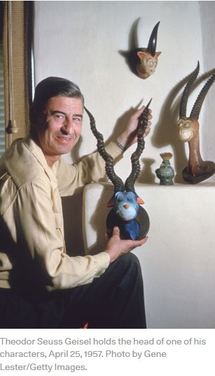

The collection on display at Pop International Galleries celebrates two decades of The Art of Dr. Seuss Collection by re-releasing previously sold-out works that span his original book illustrations, midnight paintings, and what he called his “unorthodox taxidermy.” Those sculptures, the first edition of which was released in 1999, are mounted creatures’ heads that Geisel originally created with papier-mâché and the beaks, horns, and antlers of real animals (the reproductions are resin casts). He titled them after nonsensical animals, such as Two-Horned Drouberhannis (2001), Kangaroo Bird (2006), and Semi-Normal Green-Lidded Fawn (2005).

Though they never saw the light of day during his lifetime, these sculptures demonstrate that Geisel established his unique vision early on, while he was living in New York in his twenties. He conceptualized the fantastic beasts from the animal parts he’d requested from the Springfield Zoo, in Massachusetts, after the animals passed away. The zoo was part of the park grounds where his father was the superintendent; Geisel spent much of his childhood there. “I think that, in some ways, had a profound effect on him in terms of the animals he created,” Jaffe noted.

Geisel’s time in New York was marked by many early rejections. After graduating from Dartmouth in 1925, he traveled to Paris and soaked in the arts scene at a time when

Surrealism was taking hold of the city. When he returned to the States and relocated from Springfield to Manhattan, he had trouble getting his nascent illustration career off the ground. “I have tramped all over this bloody town and been tossed out of Boni & Liveright, Harcourt Brace, Paramount Pictures, Metro Goldwyn, three advertising agencies, Life, Judge and three public conveniences,” he wrote to his friend Whit Campbell.

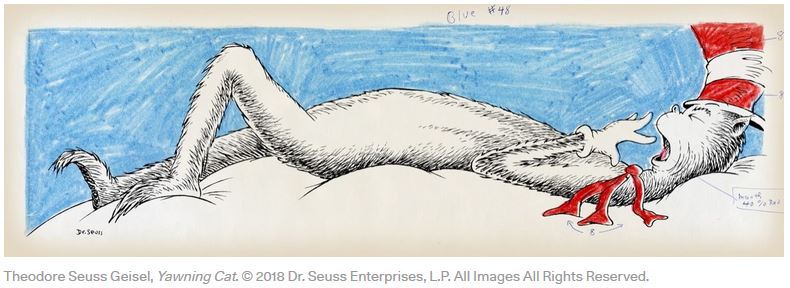

But he would make his mark in the advertising world, following a successful campaign for Flit bug spray that read “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” and featured a very Seussian insect slyly whizzing through a woman’s fancy hat. His advertising illustrations led him to a stint as an political cartoonist in 1941, as World War II came to a deafening crescendo. Before he joined the army in 1943, as a scriptwriter for a filmmaking unit that documented the war, he had already begun to write children’s books, including Horton Hatches the Egg in 1940. But he wouldn’t see international fame until years later, after moving to California; he released The Cat in the Hat in 1957, which, with its repetitive use of language geared toward beginners to reading and emphasis on phonetic learning, entirely transformed children’s books.

Though it was the innovative way he addressed reading comprehension that first made Geisel’s books a sensation, it’s the clever depth of his subject matter that has given them longevity. The Sneetches and Yertle the Turtle are allegories that explain discrimination and fascism, respectively, while The Lorax advocates to preserve the environment. The last book he wrote during his lifetime, Oh, the Places You’ll Go!, encourages readers to live life fully, and to embrace change—it reportedly returns to the bestseller list each spring when students graduate.

While Jaffe noted that it was clear Geisel loved how he made his living, he mused: “I think the secret art is the real stuff”—the pieces he was truly passionate about. Each side of his practice, however, forms a more comprehensive picture of the visionary Dr. Seuss. “I don’t think that the secret art or unorthodox taxidermy or the illustration art can be really separated,” Jaffe said. “I think they are all very much a part of who he was as an artist.”

They are undoubtedly part of the same world, one where nonsense and sagacity live hand in hand, where you’ll encounter lithe, furry trees; sinuous roads; and green eggs and ham. Geisel himself lamented the rules of the universe he had created. “If I start out with the concept of a two-headed animal, I must put two hats on his head and two toothbrushes in the bathroom,” he once said. “It’s logical insanity.”

(Source: artsy.net)

(Author: Jacqui Palumbo)